The cartography of imagination

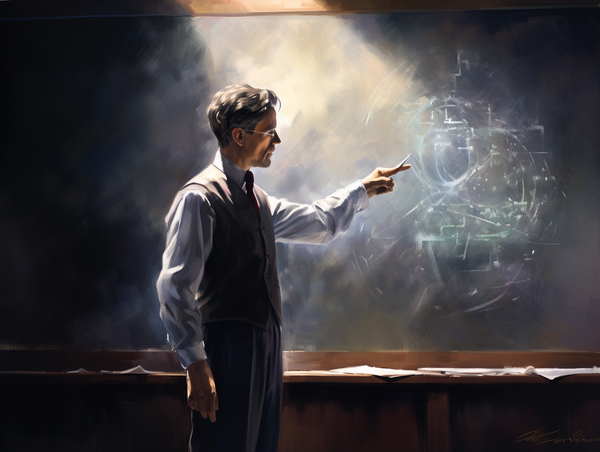

The cartography of imagination lies not in the charting but in the courage to sail beyond the edge.

Consider the humble notebook. I have nineteen of them, accumulated over many years. They are not journals in the conventional sense—I do not record what I had for breakfast or whom I met for coffee (though occasionally such details slip in, like stowaways on a cargo ship). Rather, they are repositories of questions, observations, and fragmentary thoughts that might, under the right conditions, germinate into something meaningful.

On page forty-three of notebook nine, there is a sketch of a snail I observed in a garden, carrying its home on its back with what I interpreted as tremendous dignity. Beside it, I wrote: "What if our ideas are not produced by us, but are entities we temporarily house?" This notion—that ideas may choose us rather than the reverse—has occupied me for years.

A sideways glance often reveals what a fixed stare obscures.

The best ideas, I've found, emerge not from deliberate pursuit but from a practice of receptive wandering. Instead of chasing, the trick lies in learning to place ourselves in the path of inspiration.

But, how does one do this? I cannot offer a formula, for that would contradict the very nature of discovery. But I can share what has worked for me, with the understanding that each mind is a unique ecology with its own seasons and weather patterns.

First, there is the practice of intentional digression. When researching a subject, I often follow the dirt paths that branch from it. While writing about the history of cartography, I became fascinated by the story of a 16th-century mapmaker who included elaborate sea monsters in the unexplored regions of his maps. This "irrelevant" detail eventually led me to a meditation on how we populate our ignorance with imagination—a theme that became central to my understanding.

Second, there is the cultivation of productive emptiness. The Japanese concept of ma—the meaningful space between objects—applies equally to thoughts. I schedule periods of mental fallow, during which I forbid myself from actively pursuing any particular intellectual target. I walk, I clean my bookshelves, I prepare elaborate meals requiring meticulous chopping. And in these intervals, connections form unbidden.

Third, there is the practice of deliberate naiveté. Children ask extraordinary questions because they have not yet learned which inquiries are considered sophisticated. If a child asks why is the sky up and not down, more often than not most of us won't have an adequate response.

We must relearn this capacity for fundamental questioning, peeling back the layers of assumption that accumulate with education. And age. Perhaps our most original insights come when we temporarily abandon our expertise and approach our subjects with untutored hands.

The explorer is, after all, not someone who creates new territories but who discovers what has always been there. The same applies to an explorer of ideas. We do not invent understanding so much as uncover it, brushing away the sediment of habit and convention to reveal a fossil of truth.

Depth requires descent. Just as the most nutrient-rich soil is found not at the surface but several layers down, our most valuable insights often require us to dig beyond our initial understanding. The first thought is rarely the best thought—it is merely the threshold to deeper thinking.

But how do we know when we have found something of value? Again, I have no definitive answer. There is a feeling that accompanies genuine discovery—a quiet recognition, a sense of rightness that settles in the chest rather than the head. It is not euphoria (which can accompany false insights just as easily as true ones) but something more subtle:

A cessation of seeking.

The cartography of imagination reveals these hidden connections, mapping not just what we know but the relationships between what we know.

We need to listen to what refuses to be forgotten. The idea that returns, that taps repeatedly at the window of attention—this is the one that deserves our hospitality. We need to invite it in, offer it the comfort of our consideration, and see what it has traveled to tell us.

In today's age of algorithmic content thirst traps, this approach may seem tad indulgent. But the history of human thought suggests otherwise. Our most profound advances—in science, in art, in understanding—have rarely come from linear processes. They emerge from spirals, from circles, from the unpredictable engaged mind with an elusive subject.

Perhaps this is what we are seeking when we search for new ideas—not conquests, but connections; not territories to claim, but constellations to contemplate.

And so I sit in the gathering dark, my notebooks spread around me like islands in an archipelago, each one a fragment of a larger continent of thought. I lift my pen from the page, and the ink seems to shimmer. The words I've written resemble a coastline —the curves and edges of thought marking boundaries between what is known and what remains to be discovered.

The cartography of imagination lies not in the charting but in the courage to sail beyond the edge.

I write ‘cos words are fun. More about me here. Follow @hackrlife on X or subscribe to my blog